‘la víctima principal del Alzheimer no es el enfermo sino el propio cuidador’

‘la víctima principal del Alzheimer no es el enfermo sino el propio cuidador’

[The main victim of Alzheimer is not the patient but the keeper]

Pablo A. Barredo

This is one of those sentences that send your body to a sudden stop while your mind races at the speed of light. You attempt to rationalize it, but cannot. What is going on? Does it apply to everybody and every single case? Is this a particular happenstance of our fast-paced productive-driven society?

Alzheimer’s disease (named after Dr. Alois Alzheimer) is considered the most common cause of dementia among older people, with the first symptoms usually appearing after age 60. It is an irreversible, progressive brain disease that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills, with other disturbances of cognitive function and personality change, and, eventually, even the ability to carry out the simplest tasks of daily living. Alzheimer’s is a slow disease that progresses in three stages—an early, preclinical stage with no symptoms, which most of the times goes unnoticed (Stages 1 to 4), a middle stage of mild cognitive impairment (Stage 5), and a final stage of Alzheimer’s dementia (Stages 6 and 7, if reached).

THE STAGES OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

| Mostly unrecognized(up to 10 years) | Stage 1 | No impairment evident |

| Stage 2 | Intermittent memory lapses | |

| Stage 3 | Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) | |

| Stage 4 | Trouble with trivial activities | |

| Obvious dementia stages | Stage 5 | Help is needed – Forgetful – Hazy on major autobiographical events |

| Stage 6 | Noticeable personality changes; loss of coherent sense of surrounding environment | |

| Stage 7 | Loss of ability to talk, walk, eat; bed ridden, immobile, and helpless |

According to Dr. Barry Reisberg sensu Gillies

Thinking about Barredo’s statement I discovered Andrea Gillies, a writer and journalist who ended becoming keeper of Nancy, her mother in-law. From her experience from the days spent caring for her she writes a memoir (A. Gillies. 2009. Keeper. Short Books, London and Broadway Books, New York). A memoir where, besides describing the physiological whereabouts of the disease and the ways they are experienced by the diseased, she lays bare how this very personal experience affected not just her life, but also those of each one of her family members.

Some of her concerns about the illness itself are expressed here:

The most widespread misconception is that dementia’s good way to go: “They’re in their own little world and pretty happy” (…) If I had to pick one catchall descriptor for Nancy’s life in the last few years it would be misery. Profound misery, unceasing and insoluble. She knows that something is wrong, very wrong, but what is it?

(…) Her mind [Nancy’s], unable to deal with not being able to make sense of things, makes its own sense, delivering explanations up from fragments, inventing new scenarios that make things seem coherent. (…)

There’s no cure for dementia. There’s no partial cure. All that’s available is a slowing down of the symptoms of fire damage. Sufferer’s experience of the drugs available is patchy and inconsistent. They don’t work for everyone. They’re hit and miss, and usually only of short- to medium-term use.

When Nancy is upset, distraction’s the only way out. Everything else, and especially reasoning, only escalates and intensifies the trouble.

Therefore,

People are afraid of this disease. (…) People act as if dementia were contagious, (…), and the social stigma is as strong as ever. (…) When things get difficult for old colleagues and fans, it’s easier for them to turn them away, untroubled by duty.

And then, she poses a poignant question regarding her own unrequested role:

Does anybody who hasn’t been through it understand just how dehumanizing caregiving can be?

This is, of course, a rhetorical question that refers mainly to non-professional caregivers, those thousands of ones that cannot go home by the end of the day because they are already there; those keepers who do not have breaks, weekends, or vacations because they care for a loved one; those who are caregivers 24/7, 365 days a year, and who have to pay an undeserved toll precisely because of that. Gillies continues:

I am not feeling well. This not-feeling-well feeling is persistent and low-key. I am not going to the doctor. I don’t want to have a conversation about stress and embarrass myself. Stress would be the word used at the consultation. It’s an easy word, protectively imprecise, a useful box to tip your feelings into. But a better word would be incompatibility. It’s the shock of daily, ongoing proximity to this “vegetable universe” of my in-laws: their lives pared back to the bone, to the medical, physiological, placed squarely in the raw, reduced to material struggle, an easy decline the most that can be hoped for.

Why is all this of important consideration?

- Because the risk of Alzheimer’s increases with age;

- Because beyond age 65 the amount of people with Alzheimer doubles for every 5-year interval;

- Because it is estimated that there as many as 5 million Americans aged 65 or older who have the disease; and,

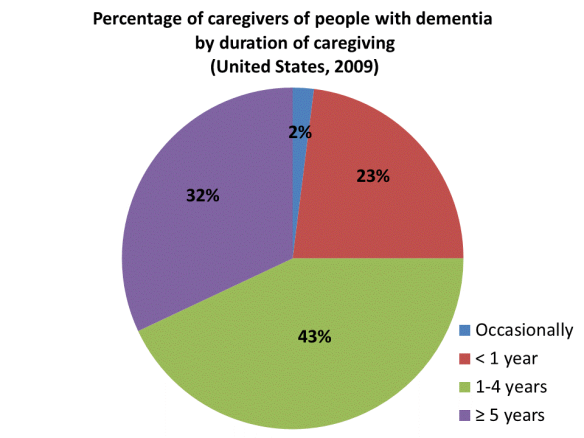

- Because unless we can find a cure or a way to prevent it, with current population trends the number of affected people will significantly increase. And with that the number of caregivers needed to care for all of them: see the following graph.

Modified from: Alzheimer’s disease Facts and Figures 2014 Report, Alzheimer’s Association, Chicago.

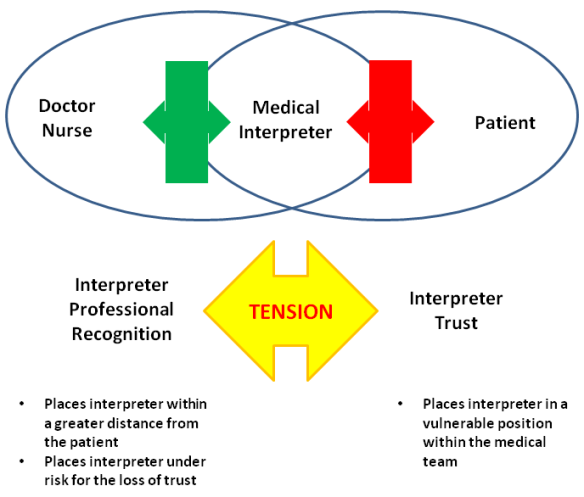

These considerations bring to mind several questions directly related to our role as medical interpreters:

- How might be this affecting the outcomes of the medical encounters where patients have to be accompanied by their caregivers and are most likely unable to speak out by themselves?

- Are there any available symptoms or cues that may serve as an indication as to what extent keepers might be psychologically worn out by their own role? And how those distress them and might ultimately affect the medical caregiving to the demented patient they care for if the most trusted information regarding the patient’s condition should be coming from the keeper?

- Are there any specific cultural cues that interpreters might be able to spot that clinicians would likely miss due to cultural differences?

- Is an intervention by the interpreter appropriate in cases as such?

I trust that interpreters can be of invaluable help in acquainting medical providers with the nuances of cultural understanding, and socially driven responses, to Alzheimer’s disease and other dementia as well as to get useful insights into the patient’s (family and friends alike) expected management of their illness. September 21st of each year has been established as the World Alzheimer’s Day; a day in which Alzheimer’s organizations around the world concentrate their efforts on raising awareness about Alzheimer’s and dementia. I was wondering how many of you did this year remember this particular date or simply knew about it and its significance. Be this note of some help towards this goal of awareness to see if we can start answering some questions.

Additional references:

- Baldwin, C. and Bradford Dementia Group. 2008. Narrative(,) citizenship and dementia: The personal and the political. Journal of Aging Studies 22:222-228.

- Maurer, K et al. 2006. Has the management of Alzheimer’s disease changed over the past 100 years? The Lancet 368: 1619-1621.

- Interview: Pablo A. Barredo: “Un enfermo de alzheimer no pierde nunca la memoria emocional” www.lavanguardia.com. [in Spanish]