Depression is a persistent brain disorder, component of various psychoses that interferes with the patient’s everyday life. Its symptoms can include: sadness, loss of interest or pleasure in activities one used to enjoy, change in weight, difficulty sleeping or oversleeping, energy loss, feelings of worthlessness, and thoughts of death or suicide.

There is no single cause for depression, among them genetic, environmental, psychological, and biochemical factors. It is estimated that in the United States alone 20 million people suffer depression with feelings that do not go away, even though antidepressants and talk therapy have been considered effective treatments.

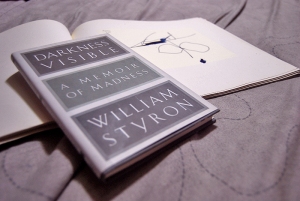

William Styron, an American writer best known for his novels The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967) and Sophie’s Choice (1979) had his worst bout of melancholia in 1985; a bout so severe that provided him with a seven week stay in the psychiatric unit at Yale –New Haven Hospital. Out of his experience with depression he wrote an article that appeared in the magazine ‘Vanity Fair’, which was later expanded and published as a book: Darkness Visible: A Memoir of Madness (Random House, 1990). There, he reflects on his knowledge of the malady acquired as a long-sufferer of this incurable and recurrent illness.

William Styron, an American writer best known for his novels The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967) and Sophie’s Choice (1979) had his worst bout of melancholia in 1985; a bout so severe that provided him with a seven week stay in the psychiatric unit at Yale –New Haven Hospital. Out of his experience with depression he wrote an article that appeared in the magazine ‘Vanity Fair’, which was later expanded and published as a book: Darkness Visible: A Memoir of Madness (Random House, 1990). There, he reflects on his knowledge of the malady acquired as a long-sufferer of this incurable and recurrent illness.

Here are some very interesting issues as expressed by him in regarding the illness and his own experience of it (underlined are mine). I trust that some of his comments about the malady are largely self-explanatory:

- Depression is a disorder of mood, so mysteriously painful and elusive in the way it becomes known to the self – to the mediating intellect – as to verge close to being beyond description. It thus remains nearly incomprehensible to those who have not experienced it in its extreme mode (…)

- My acceptance of the illness followed several months of denial (…)

- A disruption of the circadian cycle (…); this is why brutal insomnia so often occurs and is most likely why each day’s pattern of distress exhibits fairly predictable alternating periods of intensity and relief.

- (…) never let it be doubted that depression, in its extreme form, is madness. The madness results from an aberrant biochemical process. (…) such madness is chemically induced amid the neurotransmitters of the brain, probably as a result of systemic stress, which for unknown reasons causes a depletion of the chemicals norepinephrine and serotonin, and the increase of a hormone, cortisol. With all of this upheaval in the brain tissues, the alternate drenching and deprivation, it is no wonder that the mind begins to feel aggrieved, stricken, and an organ in convulsion. Sometimes, though not very often, such disturbed mind will turn to violent thoughts regarding others. But with their minds turned agonizingly inward, people with depression are usually dangerous to themselves. The madness of depression is, generally speaking, the antithesis of violence. It is a storm indeed, but a storm of murk. Soon evident are the slow-down responses, near paralysis, psychic energy throttled back closed to zero. Ultimately, the body is affected and feels sapped, drained.

- (…) certainly one psychological element has been established beyond reasonable doubt, and that is the concept of loss. Loss in all of its manifestations is the touchstone of depression – in the progress of the disease and, most likely, in its origin.

- (…) The pain is unrelenting, and what makes the condition intolerable is the foreknowledge that no remedy will come – not in a day, an hour, a month, or a minute. If there is a mild relief, one knows that is only temporary; more pain will follow.

- A phenomenon that a number of people have noted while in deep depression is the sense of being accompanied by a second self – a wraithlike observer who, not sharing the dementia of his double, is able to watch with dispassionate curiosity as his companion struggles against the oncoming disaster, or decides to embrace it. (…)

- (…), the hospital was my salvation, (…) – I found the repose, the assuagement of the tempest in my brain, that I was unable to find in my quiet farmhouse. This is partly the result of sequestration, of safety, (…) the hospital also offers the mild, oddly gratifying trauma of sudden stabilization – a transfer out of the too familiar surroundings of home, where all is anxiety and discord, into an orderly and benign detention where one’s only duty is to try to get well. For me the real healers were seclusion and time.

- Save for the awfulness of certain memories it leaves, acute depression inflicts few permanent wounds. There is a Sisyphean torment in the fact that a great number – as many as half – of those who are devastated once will be struck again; depression has the habit of recurrence.

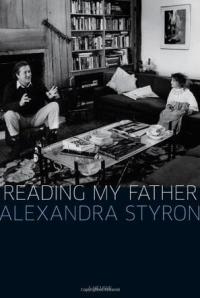

Quite recently, Alexandra Styron, one of his daughters, has reflected on her personal father-daughter relationship and how this relationship has been, over the years, shaped by her father’s illness; personal impressions and thoughts made public in Reading My Father: A Memoir (Scribner, 2011). Therefore, father and daughter provide the public with a rare case, in which the interested reader can somehow experience firsthand the effects of a given mental illness from two different perspectives: that of the patient himself and that of one his most direct (though not quite sure if close) family members. Some of her impressions follow (underlined are mine):

Quite recently, Alexandra Styron, one of his daughters, has reflected on her personal father-daughter relationship and how this relationship has been, over the years, shaped by her father’s illness; personal impressions and thoughts made public in Reading My Father: A Memoir (Scribner, 2011). Therefore, father and daughter provide the public with a rare case, in which the interested reader can somehow experience firsthand the effects of a given mental illness from two different perspectives: that of the patient himself and that of one his most direct (though not quite sure if close) family members. Some of her impressions follow (underlined are mine):

- (…) He was also praised, perhaps by an even larger readership, for Darkness Visible, his frank account of battling, in 1985, with major clinical depression. A tale of descent and recovery, the book brought tremendous hope to fellow sufferers and their families. His eloquent prose dissuaded legions of would-be suicides and gave him an unlikely second act as the public face of unipolar depression.

- (…), he flatly refused the two forms of treatment universally acknowledged as beneficial for the maintenance of a mind inclined to melancholia: talk therapy and antidepressants. (…)

- (…) Wretched and panic-stricken, Daddy began suddenly clinging to my mother as if she were the last raft on the Titanic. He’s spent more than twenty years pushing her away. Now he wouldn’t let her out of his sight. (…) If she did manage to sneak away one hour, a passing rain shower was enough to convince him she and her car were wrapped around a tree.

- (…) His voice all but disappeared, his gait slowed to a palsied shamble. The fantasies of suicide he’d harbored through much of the fall turned still more lurid – although, institutionalized as he was, he did grow resigned to the fact that the option was probably out of his hands. (…) His hyperreactive system – hitched to his chronic hypochondriasis (…); every “possible side effect” tried out its routine on him. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) was suggested as a possible option, having proved to be a particularly efficacious treatment for unresponsive, older patients.

- Watching Daddy go insane was tough on all of us but utterly devastating for my mother. His obsessions were endless and exhausting. (…) But sometimes it looked at her and it seemed as if she could not breathe, as if the whole unbearable situation would literally suffocate her. (…)

- Some days I just looked at my father and thought: Are you really going to die of depression? (…) He knew he was losing the fight, but he drew the line at being forced to feel better. No trying was his toehold on personal dignity, his last stand.

Although depression affects everybody in a different way and degree of intensity, it is noticeable from both Mr. Styron and her daughter’s comments that depression is a difficult to accept long-standing illness that strongly affects both patients and family alike. However, as with many diseases, acknowledging it is the first step to fighting it. And it is important to keep in mind that in making public a battle such that can only help other affected people to cope and fight against it, while hiding it and denying it not merely delays to the point of suppression the patient’s options for recovery but also prevents fellow patients, caretakers, and medical providers alike to benefit from our understandings.

Additional References:

Medline plus (NIH: National Institute of Mental Health);